Always on the lookout for flutes by Irish makers, or ostensibly so, I was delighted to come across a flute by Dollard, a family of makers listed as follows in the NLI

That great source of information on Irish musical instruments "The Dublin Music Trade" quotes Rose ( no relation to John Mitchell ) in relation to Isaac Dollard, and places him in the succession between McNeil and Butler "Algernon Rose (Talks with Bandsmen, London 1894, cited in Waterhouse) states that Isaac Dollard was possibly the 'Mr Dollard, maker of flute, Kent-bugle, serpent and bass-horn', who apprenticed under John McNeil (ii) and was succeeded by George Butler in 1826."

The DMT site also reveals that according to Henley,* apparently their instruments, particularly the strings, were not well thought of:-

Writing about 'Dollard' of Dublin (no first name), Henley comments:

"...worked in Dublin, 1800, workmanship very rough and utterly puerile. Varnish dull and blotchy. Outline and arching perfectly exemplify incompetency of designer. Wretchedly poor and weak tone. 'Cellos belong to same order. Some instruments known of better modelling and workmanship, but generally assumed to have been made, or at least finished by M'Neill'."

Ouch!

Finally the DMT site comments:-

"References to, and instruments made or sold by members of the Dollard family often not distinguished by name. Mark: Dollard / Dublin (Waterhouse)"

Lets look at the physical flute., this was how it appeared on eBay..

At a cursory glance it might appear like a fairly standard 8 keyed flute, but a closer examination, shows some interesting differences.

Firstly, the foot.

Two things are immediately different from the normal 8 keyed foot, although the principal of two touches operating two open standing keys is maintained. Firstly the two open standing keys operate at right angles to the normal system where they run along the flute. Secondly, the two touches are stacked above each other as opposed to the normal side by side. Let's just remind ourselves of the normal setup.

This the foot of Rudall & Rose #1376

A third thing which is probably the most remarkable about the foot, is the location of the Eb key, which is to the left of the C and C# touches, looking from the head, i.e. in exactly the opposite position to normal.

Some other small aspects of the flute are worth mention.

Apart from the foot, the key set up is what one might call typically French...the G# being a cross key, which runs under the long C which is arched to allow this. In this case, another notable feature is the fact that the Bb block is separate from the long C support, the usual way of doing things.

N.B. the very long tenon

Also note the rather unusual "doughnut" seatings.

With regard to the keys, it's only when the pads are removed that another unusual feature is revealed. Each key has a little spike, which appears to be threaded, descending internally from the apex of the cup. Their function is unknown.

Here's an image of one of the pads, showing the little hole in the shellac backing up the purse pad. Again it's hard to see what this achieves.

In the case of this particular flute, it appears that the foot joint keys have had the spike removed, but it's still possible to see its base. N.B. also the little flat just where the shaft comes in. This indicates to me that someone as tried to readjust the angle of the cup by bending the shaft towards the cup.

Finally, in this catalogue of divergence, the barrel joint is unique.

In all the Dollard flutes that I've seen or heard of, the construction of the tuning slide - and I don't think this is an exaggeration,- is the most unusual of any maker.

Essentially the construction of the head is quite normal, given that Dollard seems to have favoured the half lined head. In this case the head liner is silver. The barrel though is quite different. There is no liner tube in the barrel. Instead, the barrel is lined with cork, so that the slide is formed by the head tube sliding within this cork cylinder, a system which works surprisingly well.

Here it is as it came to meand with the slide mount and old cork removed

( the mount was held in place with three little silver pins which had torn out when the mount was removed.)

And here it is with the cork replaced

The flute was in really very good overall condition, there were no cracks in either head or barrel ( a consequence of the half lined head and cork lined barrel?) which are almost standard in a flute of this age. Otherwise two blocks were damaged and had to be replaced, and the long F key was missing, as was the ornate ring at the top of the head.

The missing ring was the most challenging thing. Normally with flat or half round or even profiled rings, it's simply a matter of finding or drawing a suitable wire and if necessary turning a profile on it.

In this case the broad decorated ring can't be reproduced in this way. Many 19th century makers, particularly in the first half of the century used this type of mount, which were bought in from outside suppliers. They would have been supplied as a long strip which was then soldered to form rings of various sizes.

I got around this problem by having a casting made of the ring which was closest in size to the one I wanted to replace. It was slightly too small but was easily expanded on a ring expander, castings being soft.

The block replacements, using old cocus, worked out well...

And the replacement long F turned out well too, thanks to images shared by Paul Bell, who has exactly the same flute as this one...but in ivory.

Researching this flute, it soon became obvious that this strange key system identified this as a flute inspired by the French player and teacher Louis Drouet.

It's perhaps worth quoting the NLI entry for Drouet.

" International virtuoso player, teacher, composer for the flute; 1817 left Paris to settle in London; 1818 established flute manufactory, employing Cornelius Ward; 1819 the business failed and, leaving Ward to supply his flutes, returned to resume his career abroad. Lindsay, warning in 1828 of the counterfeiting of flutes then prevalent in London, wrote; 'the same system has been followed in regard to Mr. Drouet's manufacture, & the comparatively inconsiderable number of flutes which his short sojourn in this country enabled him to finish, has, even on a modest computation, been thus surreptitiously increased five-fold, for notwithstanding all the 'fine toned Flutes by Drouet', which are ticketed up on every street, scarcely a genuine Drouet is to be met with."

Researching Drouet, and in particular the system of foot joint keys that he favoured, opened a rather large can of worms.

First it's perhaps necessary to understand the position that Drouet held in the musical world of the time.

Rockstro, on his own account says:

"Opinions might have been expected to vary as to the merits of an artist of such peculiar qualifications as those of Drouet, and, as a matter of fact, he was extravagantly praised by some critics, and unjustly assailed by others, but there can be no doubt that although he possessed neither the elegant style of Tulou nor the commanding tone of Nicholson, he was one of the most remarkable flute-players that ever lived. "

and in terms of his exciting the opposites of praise and opprobrium Rockstro quoting Fétis:

"He excelled in difficult and rapid passages; his double-tougueing was marvellously voluble, but his intonation was false, and his style was destitute of expression and majesty"

and on the other hand, quoting W. N. James:

"He is intrinsically and superlatively the best player on the instrument in the world

...he soars above the rest, like an eagle above the hawk, and no one seems to question his superiority

....It is impossible to imagine anything so positively beautiful as the tone of M. Drouet"

One thing that the critics seem to agree on was his ability in the areas of articulation and execution, and if it's safe to assume that Drouet was playing one of his own flutes, one has to wonder how much of that articulation and execution used the foot joint keys.

In 1828 Drouet published his Flute Method, initially in French, but with German text alongside in the 1829 edition. An English version was produced in 1830.

From my point of view, what I found interesting is the reproduction of the key work in this publication, which certainly seems to indicate that he not only played on, but recommended his odd system of foot keys.

As you can see the rather crude illustration shows a foot joint set up as in the Dollard flute, here in close up...

with the Eb key on the far side of the C and C# touches. The apparent extreme awkwardness of this set up led me to seek out other images of Drouet flutes, and this is where the worms really started to escape!

It seems that there are many variations on the basic "stacked" C/C# touches approach. One of the first things I noticed was that the Eb key is not always on the "wrong side" as it were. Initially I thought that I was looking at a left handed version of the key work, but the Eb is the only key that is changed. Here's an example from the Dayton C. Miller collection in the Library of Congress (DCM 0347), this flute stamped Drouet.

The other great source of variation is in how the C/C# touches interact with each other.

Here's a couple of Drouet feet illustrating this.

This one is by Holtzapffel (Jean Daniel, brother of the author of " Wood Turning and Mechanical Manipulation ) and you can clearly see that there is some sort of device which appears to help the C#/C touches act together. and in close up

Again here's another example, this time from

Charles Sax.

and again in close up.

It's really no surprise that other makers have tried to modify the original Drouet system, in fact some of the Drouet flutes moved the Eb to the "right" side, as per the example above, and it should also be noted that both the C/C# and Eb touches vary in that sometimes they are curved towards one side, sometimes the other.The system of the stacked keys seems to have been problem ridden from the very start. Rockstro commented on a flute by Drouet...

" the arrangement of the keys of the foot-joint is peculiarly complicated and inconvenient"

In this case he wasn't far wrong.

Let's look at the fingering of the foot joint keys with the original set up where the Eb is on the far side of the C#/C touches. As someone used to the normal simple system foot joint the only way I can see that this set-up can be used is to turn the foot towards the player to the extent that the Eb touch is on top of the flute, just about in line with the finger holes. This allows access to the Eb without the danger of hitting the C/C# touches.

How to manipulate these though? In the vast majority of flutes that I've looked at, the problem of moving from C# to C or vice versa attempts to be solved by curving the C touch up to meet the C# as seen here on Paul Bell's ivory Dollard.

So assuming that the foot is turned inwards sufficiently to allow access to the Eb key, the sequence Eb-C-C# can be played by using the finger tip to open the Eb, and then the first joint of L1 to depress the C touch, which will of course also close C#. Then rolling the finger to the left opens the C key and pressure being still on the C# touch, C# results. A bit awkward but doable. But what about the sequence Eb-C#-C, or in fact any sequence where C must be played after C#? If the C# touch is suppressed, this leaves a gap of 1mm or more between the C# and C touches, and the finger must somehow negotiate this without lessening pressure on the C# touch. This is presumably what the modifications on the Holtzappfel and Sax were meant to accomplish. Complicated and inconvenient doesn't go quite far enough!

In the case of my Dollard, there is no apparent attempt to connect the C and C#, which removes all possibility of playing C after C# without not only gap between the notes, but also the little finger would have to be taken off the C# making the sequence C#-C into C#-D-C.

I did consider the possibility that the C# touch had been bent down from the more common arrangement, but there is little evidence of this on the key.

Finally, there is one other strange aspect. On Paul Bell's ivory Dollard, which is the only other flute from the same maker with the same key system to which I currently have access, one spring, that on the C touch serves both it and the C# touch, and for this to happen the C touch must curve up and make contact with the C#.

On my Dollard however, despite the fact that the keys don't touch at all, there is a spring on the C#, and what's more, the end of the spring goes distinctly beyond the axle hole, meaning that the key operates in the opposite direction to usual...e.g. a long C sprung in this way would stand open, not closed.

Maybe it's best to illustrate this.

Here's Paul Bell's C# touch

and mine

and here's the position of the key that the long spring induces.

Currently, I can see no sense in this arrangement, as it makes absolutely no difference to the original set up. It would have made more sense if the C# touch was sprung normally and the C touch fitted with a 'reverse spring', which would have the effect of keeping the C and C# touches touching...if that makes sense. This would, of course, cause all sorts of other issues for the operation of the keys though. This 'additional' spring does seem to be a later addition, as it's a steel spring whereas all the others are brass.

The whole concept of the facility with which a player can negotiate the notes provided by the foot joint keys is something that fascinates me as a flute maker.

Continental makers in particular, were keen to pursue the downward extension of the flute scale. I've never seen an English flute which goes below Bb...using four keys to be operated by the right pinky, whereas some Viennese and North Italian flutes descend as far as G, with complex arrangements of keys for both little fingers.

Many flute scholars, myself among them, would argue that these keys ( certainly the ones giving notes below B ) were more for show for the maker and/or the player, than of any practical import.

While I was working on this flute, I was given one of my own 8 keyed flutes from 1995 for overhaul. It used a system of foot joint keys which I haven't seen anywhere else, (although I stand open to correction) and which I only used once or twice. It's only when I was working on this blog that I saw the partial similarity between this...

...and Drouet's system.

One can't be sure at this remove what Drouet's intention was, but mine was to simplify the C and C# touches. The C# touch is never a problem, but it's how to get around the C# cup/pewter and onto the C cup that's the issue. Up until the late 18th century the 'up and over' method, as seen on Potter's flutes was commonly used. This was superceded by the 'out around the side and back in again' system which was universal in the 19th century, as seen on the R & R foot illustrated above.

My idea was not to use either of these systems, but use two straight touches, which radically cuts down on the amount of time taken to fabricate the keys....and it's almost as easy to make the C# operate at right angles to the bore as along it.

Finally, back to the Dollard. When I was first stripping the flute down in preparation for the restoration I was amazed to see what looked like small neat lettering under the low C touch. Careful cleaning showed it to be...dirt!

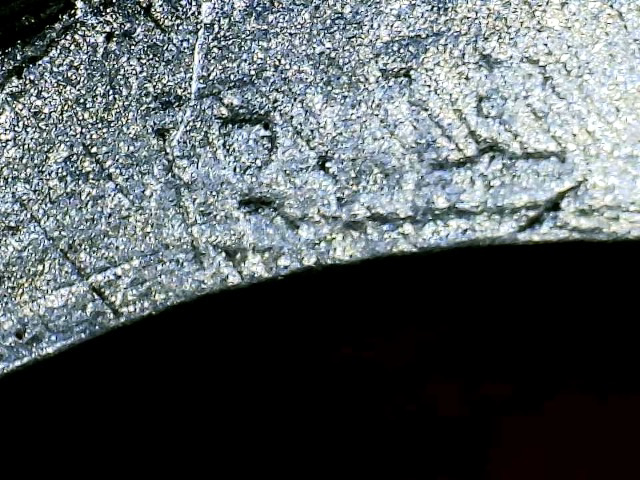

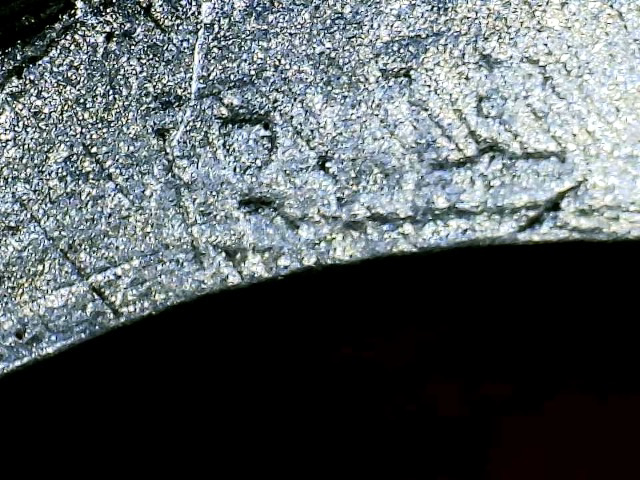

However, when I was applying the cork lining to the barrel, I had taken off the ring at the top of the barrel, and this time there was no mistake. On the lower surface of the complex ring, the surface that bears against the top wooden rim of the barrel, there were three letters stamped.

I think the only distinct letter is the one to the right...X. The left hand one is probably R, but could be B. The one in the middle is hard to figure.

Is it E? Is it another R? In the first pics above it does appear to be E, and therefore the whole sequence to be REX. Here's a couple of other views...

Why stamp these letters in a place where they would never have been seen unless the flute was dismantled for restoration? I suppose we'll never know. I'd really appreciate any input on this in terms of either a better reading of the stamp, or the significance of the letters.

Thanks to Jem Hammond and Paul Bell for help with images.

*Henley, William and Cyril Woodcock, Universal Dictionary of Violin & Bow Makers: Price Guide and Appendix, VII. Brighton: Amati Publishing, 1969.

|

|