It's well known among old flute enthusiasts that the famous firm of Rudall & Rose was founded in 1821 by the flute teacher George Rudall and the flute maker John Mitchell Rose. However it's the flutes that George Rudall had made in the few preceding years by the maker John Willis, and in particular one of those flutes, that is the subject of this post.

It was a very common arrangement for well known "professors" of the flute to associate themselves with a particular maker, and would provide these flutes to their students and others, and in this case Rudall chose his collaborator well.

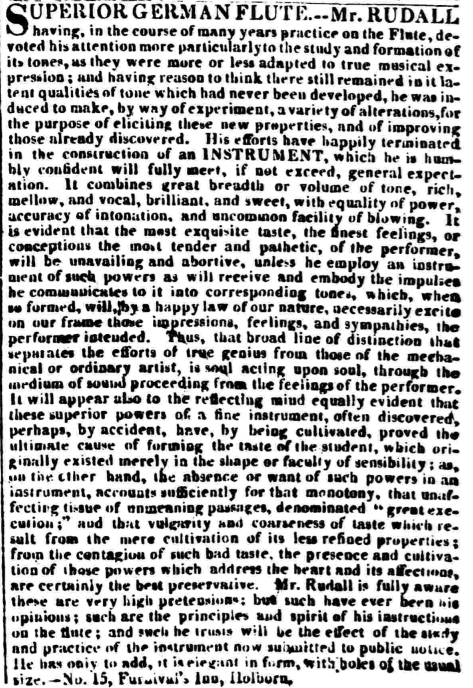

John Willis came to prominence as a maker in the early 19th C, someone who made flutes for resellers, but operated on his own account from several addresses. Here's what the NLI has to say:

John Willis had a younger brother, Isaac who initially operated from Dublin, taking over from the Goulding d'Almaine & Potter operation there in 1816, later moving to London. I hope to reveal more about Isaac in future posts about the Dublin woodwind trade, but I'll leave it till then, since his relevance to this post is simply to acknowledge him as John's brother. It's thought that Isaac was purely a reseller, and never made on his own account.

When did John Willis make the flutes for George Rudall?

Rockstro says that he resigned his commission in the army ( he had been a Lieutenant in the Devonshire Militia ) around 1820 and commenced as a flute teacher and supplier of instruments at that time. However there is quite a lot of evidence to contradict this, which shows that he was a flute teacher by 1816, and this might help explain why many of these flutes survive. This has been discovered recently:

This seems to suggest that he was providing flutes by 1816, and the details of the famous court case, as related by Robert Bigio, also show that he was teaching music by that date. I had always thought that a remarkable number of the Willis Fecit flutes survived given that the supposition ( stemming from Rockstro and repeated in the NLI ) that he didn't leave the army until 1820, and formed Rudall & Rose in 1821, but a period of 5 years does make more sense in terms of the number of surviving instruments.

One aspect of this that has always struck me as odd, is that while Willis was a well established maker, making flutes of superb quality, Rudall chose to move to another supplier for his flutes and he chose someone who had little or no reputation as a maker. John Mitchell Rose is a mysterious figure about whom really very little is known, given that he was one of the major figures in the 19th century English flute community.

I'd advise reading Robert Bigio's account of him in his " Rudall, Rose, and Carte. The Art of the Flute in Britain".

There are several other interesting aspects of the flutes that Willis made for Rudall. Firstly, given the relatively short period that the association lasted, a surprising number of the flutes have survived. Secondly, the degree of variation between the individual flutes is remarkable. This is most noticeable in terms of the style of key work, for example in the two DCM examples, one has padded keys and pewters on the foot, and the other has pewters throughout, and an "up and over" C#/C mechanism, very much in the style of Potter.

I've also seen examples with square flap keys, and I've one in my own collection which appears to have been originally made for flap keys, but converted to pads. Most of these flutes are 7 keyed, missing the long F, but mine is an 8 keyed with some other rather quirky variations, e.g. the blocks are lined except the main long F block, even though the guide block is! This I'm sure is entirely original.

The woods that Willis used were standard for the time, boxwood, and cocus, for the most part, but this particular flute is made from neither, but rather one of the woods from the Caribbean genus Platymiscium.

Having worked in flute restoration for over 40 years gives me some insight, I believe, into the woods that the old makers used. The vast majority, of course are either boxwood (Buxus sempervirens), or cocus (Brya ebene), with the occasional appearance of ebony ( Diospyros spp.), and rosewood and African blackwood (Dalbergia spp.). One confusing aspect of wood nomenclature ( see my post -A Wonderful Confusion ) are the wildly inaccurate descriptions of wood type in auction catalogues, and very often even museum catalogues. In fact it's only with long experience, and some botanical training that one begins to be able to be confidant about identifying these woods and to realise that there is another timber which was quite widely used.

It's only relatively recently that I began to realise that this timber was turning up in my restorations more and more often, and in very high quality instruments as well, and from diverse sources including London, Vienna, and New York.

So how to recognise it? One of the really characteristic "tells" is the presence of chatoyance, which in itself requires an explanation. Look at this video first...( and apologies for redirecting to YouTube, for some reason Blogger would not allow me to upload the video directly)

This in fact, is the barrel of a Hudson Pratten. The optical illusion that there appears to be "depth" to the surface, almost as if there were a very heavy coat of clear varnish and we're looking through that to a grain pattern that is actually below the surface is the essence of chatoyance. The term in English derives from the French Oeil de Chat - cat's eye, and this is obviously related to the term tiger's eye effect that you'll see used to describe the same phenomenon. If you're still unclear about this, think of the beautiful rippled figure that you'll see on the maple back of a quality violin, and how it actually appears to be below the surface.

The second "tell" which can be seen with the naked eye is the presence of very large pores in the end grain, but given that end grain on flutes is very often coated with grease and various finishes, this is not always obvious. Here, for comparison, is the end grain of cocus,

and that of Platymiscium

I think you'll agree that they look quite distinct. These images are x50 magnification

However, this is not the place to go into any more detail about the type of wood. I just wanted to establish that we're not dealing with what most people might assume is an instrument made from highly figured cocus.

So let's get to the flute itself...

and the stamps...

Here on the barrel

This image also shows the extremely high finish which characterised the flute, and which in fact allowed the chatoyance of the grain to come to the fore. It's also noticeable that the stamp was applied after the finish was complete. I have to comment here re the crooked stamp, that it remarkable how often one sees this on really high quality flutes...and it also reveals that each line of the stamp was a separate tool.

And here's the foot, with the "Willis Fecit"

The flute is eight keyed with pewter plugs on all the foot joint keys, but the other five keys are somewhat unusual in that they bear a close resemblance to the type of keys one sees on many Monzani flutes from the same period. This is essentially a development of the flat "flap" type key, but where the key shaft and the flap are two distinct elements. These photos show the basic idea.

...and this, which is actually the newly made long F key, shows the details of how it's put together,

Here, for comparison, is the Monzani set up.

Things to note here are:

1/ The screw which holds it all together is riveted through the key shank. You can see evidence of this in the middle of the crown stamp.

2/ Note the milled edge of the disc, a typical Monzani feature... and from left to right: the washer holding the leather pad in place, the leather pad, the silver disc, N.B. little washer between the disc and the key shank, and finally the key shank.

3/ The two little holes in the washer to allow is easy removal and replacement.

Let's look at the key work in general. It's fairly standard but there are some interesting features. At first glance, it appeared that this had originally been a seven keyed flute and that the long F was a later edition, mounted on a silver saddle.

The fact that the key "cup" arrangement is different to the other keys as illustrated might be another indicator that the key is an addition, as in this case its integral with the key shaft, but seems to have been added to original shaft.

However, those familiar with how blocks were reinforced on many 19th c. flutes will notice the two silver spots on either side of the long F. These are the ends of a threaded pin which was added to strengthen the block, and are incontrovertible evidence that there was a long F on this flute originally. In fact, I think that the silver "saddle" which appeared to be a means of adding the extra key, is in fact the silver block liner of the original key. These pins are more often steel, but in this case are silver.

More of this later, but there's one other aspect of the keys that is unusual, the separation of the long C guide block, and the Bb block which are normally conflated in the same block.

I've seen this arrangement on several flutes, but it is unusual. I think I'm begining to see a pattern, but I'm not going to reveal my hand...yet.

Overall, the flute was in really very good overall condition. It was playing very well when it arrived to me, and the only potential issue was the very fine crack in the head.

However the owner asked me to restore the flute to its original state, including restoring the long F key and its block.

The first job was to deal with the crack in the head. This is what it looked like on arrival...

The highly reflective nature nature of the finish, made this flute very difficult to photograph, but you can see that the crack appears to be reasonably recent, and therefore clean, without any material, dirt or grease, in the crack. This makes the repair so much easier.

As usual, far more time is spent in the cosmetics rather than the actual repair, but time well spent, I think. Here's the result.

Replacing the long F block first of all required sourcing some Platymiscium, which I did from

www.rarewoodsusa.com. who I can highly recommend. There are many species in the Platymiscium genus, and it's impossible to separate them at a timber level, but one of the most suitable for our purpose is Platymiscium yucatanum, so that's possibly the timber I used for this.

The first job was to remove the block liners, milling out sections which matched the length of the block liners, which of course allowed my to replicate the original height of the block.

Here you can see the block support pin, which I carefully milled around as I wanted to re-install it.

With block replacement work of this type, the basic physical work can often be only a small part of the process. The cosmetic work is what takes the time.

In this case, several unusual factors complicated this. Firstly the type of wood, which took some time to source. Secondly the very high gloss finish was not easy to reproduce. Also important here is the wide variation in the grain pattern of Platymiscium, which can vary from tight non "flamed" grain to very open grain with large light and dark patches interacting. Normally, I spend quite a bit of time matching the piece of timber I'm going to inlay with the grain where it's going to be inlaid, but this process can be a lot more difficult with Platymiscium. Here are the results...

The lighter coloured timber tended to be at the tops of the blocks, so I tried to match that with the new long F blocks.

Here's a view from above, and it leaves me thinking that the liner of the support block is not original, as the gauge of silver used is considerably thicker.

This also shows the finished new long F key, and I'll just re-show the rather complex elements which go to make up what is essentially a flat flap key.

From left to right these are:

1/ The key shaft itself.

2/ The main section of the key which carries the leather pad.

3/ The washer which holds the leather in place, with the two little holes which allow it to be turned securely into place.

4/ The threaded pin which holds it all together.

Here's the washer on one of the old keys, with an original Monzani screwdriver. You can see that they don't quite match, but you get the idea.

Working in such small scale is difficult at the best of times, but the major challenge here was threading the little pin. It turned out to be as near as dammit to a 1.6mm thread, which amazingly is one of the very small metric taps standardly available.

The problem here was that silver of such small diameter has little tensile strength, and kept breaking off when tapping. Next time, I'll try to work harden it, or try a bit of heat treatment.

Working with such gorgeous instruments as this, and in a way to be looking over the shoulders of the original makers, as I do the work, conscious of the way they went about theirs, is one of the great privileges of this job.